Like most of you, I'm a member of a number of online forums that talk about various aspects of creative life, everything from the business side of things to more technical how-to's. One question that crops up often is whether and how to put one's art into brick and mortar shops on consignment. Since I am both an artist and a gallery owner, I thought I'd put together a few tips for anyone who might be considering going this route.

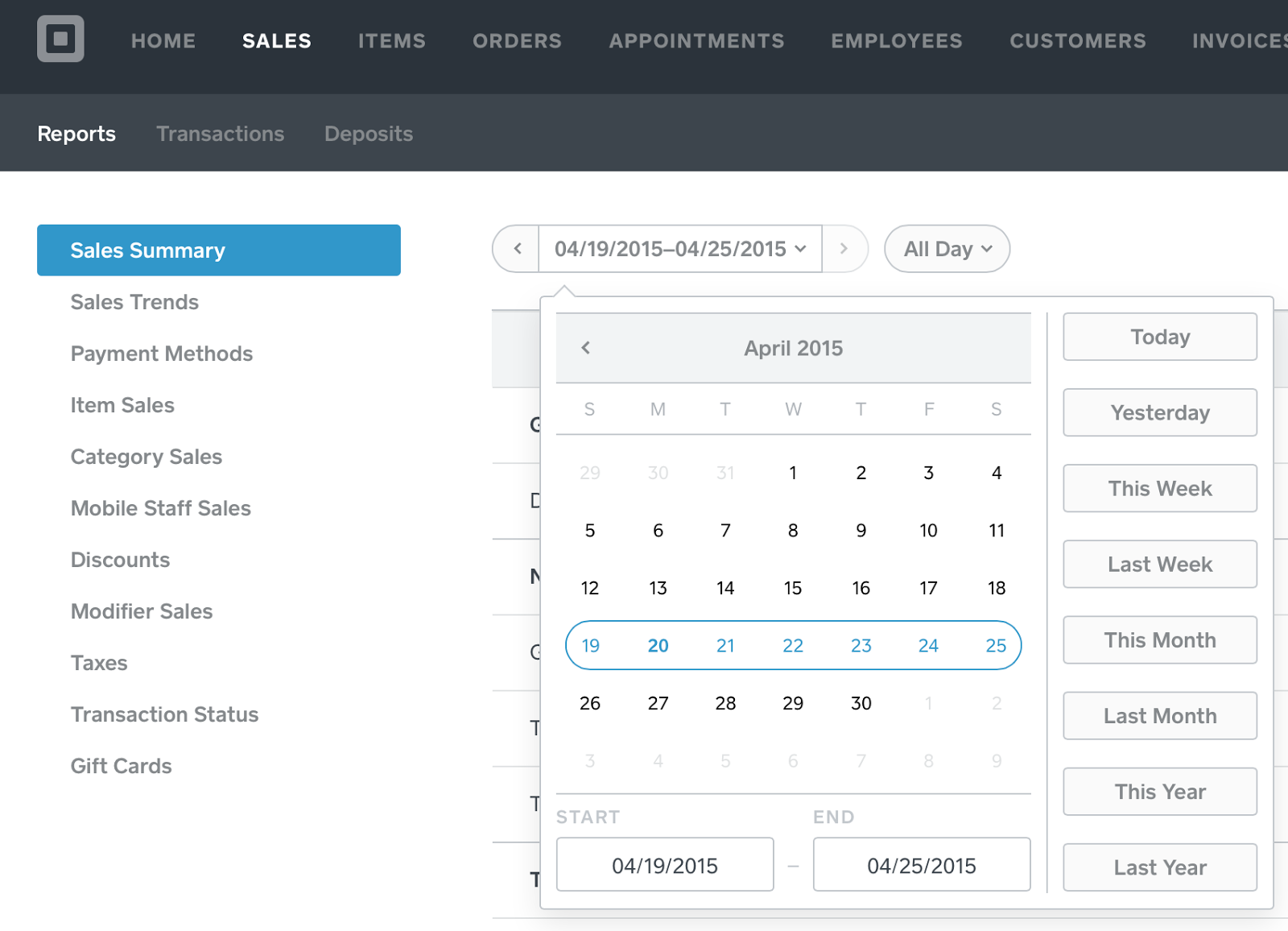

What is consignment?

It's important to understand what the consignment arrangement entails. You retain all ownership of your work, which you temporarily loan to the gallery or shop for them to sell on your behalf. When they sell the piece, they pay you the sale amount, less an agreed-upon consignment fee to cover their operating costs. This arrangement is not the same as wholesale selling, where you are paid up front for your work for a price less than what you would sell it to the general public.

What are consignment fees?

I've heard a lot of people say in online discussions that they think consignment fees are a rip off. I get it: you've worked hard to make something lovely and giving 25%, 40% or even 50% to a shop to sell it for you feels painful. But with so much of the jewelry market having moved to the virtual world in the last few years, it's easy to forget what goes into the traditional sales model, starting with all the overhead. A gallery pays rent and utilities, maintains a website, sends out emails and promotions, pays advertisers, and pays staff, taxes, and insurance. They do that before they have sold a single item, which then incurs credit card fees and packaging costs (even if it's just a small shopping bag). If you were going to sell "in person" (as opposed to online), whether you were selling at a market venue or opening a store of your own, those are all expenses you would incur on your own. Those expenses would, in turn, either increase your per piece price or reduce your overall profit. Either way, they'll cost you something in the form of booth and credit card fees, packaging, displays, transportation to and from, and - potentially - loss from theft.

|

| The Roadhouse Arts Gallery, all decked out for the holidays. Everything you see is consigned to us. |

How should I pick a consignment partner?

More than any other thing, I think this is the most important decision. It does you no good to have your inventory (read: dollars) tied up where it will not sell. Here are some of the top questions you should be asking when you're evaluating potential consignment partners.

- What is their target market? There is a difference between a fine art gallery, a gift gallery, and a fine craft gallery. I am not saying that one is better than another - but I am saying that they work within different price ranges and target different clientele. Does your work fit the overall "vibe" of the shop? Is the work by other artists of comparable quality to yours? Where do your prices fall in the overall offerings of the shop? For example, if you are a maker of boho chic jewelry, you probably don't want to be in a sleek, modern shop with lots of steel and glass. If your work generally sells for $200 and $300, you don't want to be in a shop where they mostly sell things under $100.

- What are you getting for the consignment fee? One of the commenters on a recent forum discussion told a story about a gallery that wanted a 40% consignment fee... and she was responsible for coming in and cleaning her jewelry to make sure it was presentable. Let me be really clear here: any gallery or shop that doesn't attractively merchandise your work and keep it clean for their customers doesn't deserve to have your work. Period. The consignment arrangement is intended to be a win-win for both artist and shop - you are providing quality inventory at no up-front cost to them, in exchange for which they offer you an appealing, professionally managed storefront in which to sell it and access to their customer base. They should also be handling credit card fees, packaging, and displays.

- Is there a contract? Never, ever, under any circumstances, do business with a gallery or shop that won't put your agreement in writing. Ever. Make sure you are very clear about what is covered by the consignment fee; how often you can change out your inventory; how loss by fire or theft will be handled; when you will be paid for sales; and who is responsible for paying transportation of the goods to the gallery or shop and back to you. Make sure someone at the gallery signs off on a written inventory of the items you deliver to them, so you have something for your records. Ask how often you can get an updated inventory from them of the things they still have on hand - and then make it a priority to compare that list with the sales you've been paid for so you can catch any losses early in the process.

|

| An early glass display at Roadhouse Arts, featuring work by Lisa Meyer and Gail Stouffer |

What if I can't afford to pay a consignment fee?

I recognize that pricing is a touchy subject, but I'm going to wade in and be as direct as I am able: most makers of high-quality jewelry aren't charging enough for their work. And here's why: because they are undervaluing their time. There are all kinds of formulas out there about how to calculate your pricing, but at a minimum your wholesale price needs to include something for your materials, your time to produce the piece, and profit. Yes, profit. If you sell wholesale - or consignment - you need to be able to make a profit on the wholesale price. How many times have you heard (or said yourself) something like, "I don't care about my time... as long as I make a little something more than the cost of the materials." Two things: your time has value, and profit isn't a dirty word. If a 40% or 50% consignment fee means you won't make any money on your piece, it may mean your pricing is too low.

That said, I recognize this easier said than done. You obviously have to keep the market in mind as you're selling. If you're just starting out and you don't yet have a workflow in place that lets you capitalize on efficiencies or repetitive processes, your pieces will have more time in them - and that will make them more expensive. Focus on creating designs based on techniques you have down cold, so that the cost of your time doesn't skew the end cost of the piece, either on the high side or the low side.

One other comment on pricing: never, ever undercut your consignment pricing. What your pieces sell for at a consignment shop or gallery should be exactly the same price that same piece would sell for online, at a show, or off your bench. Remember that when you sell through a consignment shop, you're saving costs you would pay if you sold it yourself: packaging, credit card fees, postage, listing fees, promotional discounts, etc.

What if things go bad....?

Take a deep breath, keep your cool, and stay professional. Every consignment agreement should have a duration - your things stay with them for 90 or 120 days and then everyone touches base to see if it's working. If the sales aren't what you expected, have a conversation with the owner or manager about what is selling and see where your things line up. Is it a price issue? Style? Quality? These kinds of conversations can be really valuable, because they can be (can be) objective feedback that will make you better in the long run. That said, if the shop isn't keeping up their end of the agreement - the displays aren't being refreshed, your jewelry is dirty or untagged, you aren't getting paid, whatever - pull your stuff.

And... make absolutely sure you're doing your part. Do your pieces reflect your best work? Is it being delivered when and how the shop or gallery has requested? Are you responding promptly to requests for information or more inventory?

* * * * * * *

This is the tip of the iceberg - there are obviously many details I haven't covered here, and honestly... consignment isn't for everyone. I took an unofficial poll of my AJE teammates before writing this post, and they were about evenly divided between happy experiences and horror stories. Remember to never put all your eggs in one basket - the trick to making a living as an artist is to develop and maintain multiple streams of income. Consignment is just one element of a long-term business strategy. Hope this brief summary was helpful!

Until next time -